The following points highlight the top four Volumes of Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology.

- Bergey's Manual Chart

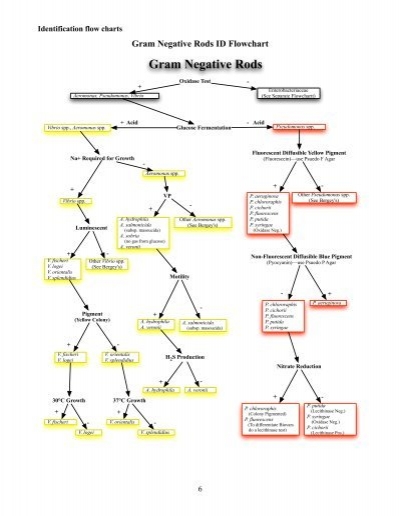

- Bergey's Manual Identification Chart

- Bergey's Manual Flow Chart

- Bergey's Manual Chart

- Bergey's Manual Chart Gram Positive Rod

Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology # Volume I:

Section 1: The spirochetes

Order I. Spirochaetals.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The following points highlight the top four Volumes of Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology. Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology # Volume I: Section 1: The spirochetes. The below mentioned article provides an overview on Bergey’s manual of systematic bacteriology. Bergey’s manual, which first appeared in 1923 and, at present, is in its 9th edition under the title Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, is a major taxonomic treatment of bacteria (prokaryotes). This manual has served the comm. Landcare Research New Zealand Ltd., Mt. Albert Research Centre, Private Bage 92 170, Auckland, New Zealand. Search for more papers by this author. The Bergey’s manual of determinative bacteriology. It has been a widely used reference since the publication of the first edition in 1923. Multiple editions of Bergey’s Manual of Determinative Bacteriology, published between 1923 and 1994, organized bacteria in groups by phenotypic characteristics, with no attempt to sort out higher phylogenetic relationships. The Biodiversity Heritage Library works collaboratively to make biodiversity literature openly available to the world as part of a global biodiversity community.

Family I. Spirochaetaceae e.g., Spirochaeta.

Family II. Leptospiraceae e.g., Leptospira.

Section 2: Aerobic, microaerophilic, motile, helical, vibroid, Gram negative curved bacteria, e.g., Aquaspirlllum, Azospirillum, spirillum .

Section 3: Normotile (or rarely motile), Gram negative curved bacteria.

Family I: Spirosomaceae, e.g., spirosoma.

Section 4: Gram negative aerobic rods and cocci.

Family I: Pseudomonadaceae e.g., Pseudomonas.

Family II: Azotobacteraceae e.g., Azotobacter.

Family III: Rhizobiaceae e.g., Rhizobium.

Family IV : Methylococcaceae e.g., Methylococcus.

Family V : Halobacteriaceae e.g., Halobacterium.

Family VI: Acetobacteriaceae e.g., Acetobacter.

Family VII: Legionellaceae e.g., Legionella.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Family VIII: Neisseriaceae e.g., Neisseria, Beizeriuckia.

Section 5: Facultatively anaerobic Gram-negative rods e.g.,

Family I: Enterobacteriaceae e.g., Escherichia, shigella, salmonella, klbsiella, Yersia.

Family II: Vibrionaceae, e.g., Vibrio.

Family III: Pasteuellaceae e.g., Actinobacillus Haemophilus.

Section 6: Anaerobic Gram negative straight, curved and helical rods.

Family I: Bacteroidaceae e.g., Bacteroides.

Section 7: dissimilatory sulphate or sulphur reducing bacteria e.g., Desulfuromonas, Desulfobacter.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Section 8 : Anaerobic Gram-negative cocci.

Family I: Veillonellacae e.g.,veillonella.

Section 9: Rickettsias and chlamydia orders

Order I: Rickettsiales.

Family I: Rickettsiaceae e.g., Rickettsia.

Family II: Bartonellaceae e.g., Bartonella.

Family III: Anaplasmtaceae e.g., Anaplasma

Section 10: Order I: Mycoplasmatales

Family I: Mycoplasmataceae e.g., Mycoplasma, ureoplasma.

Family II: Acholeplasmataceae e.g., Acholeplasma.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Family III: Spiroplasmataceae e.g., spiroplasma.

Section 11: Endosymbiont.

A . Endosymbiont of Protozoa, Ciliates, Flagellates, amoebae.

B . Endosymbiont of insects .

C . Endosymbiont of fungi and invertebrates other than arthropods.

Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology # Volume II:

Section 12: Gram positive cocci.

Family I: Micrococcaceae e.g., Micrococcus

Family II: Deinococcaceae e.g., Deinococcus.

Section 13: Endospore forming Gram-positive rods and cocci e.g., Bacillus, Clostridium.

Section 14: Regular, non-sporing, Gram positive rods e.g., Lactobacillus, Renibacterium.

Section 15: Irregular, non-sporing, Gram-positive rod, e.g., corynebacterium, Microbacterium.

Section 16: The Mycobacteria.

Family: Mycobacteriaceae e.g., Mycobacterium

Section 17: Nocardioforms e.g., Nocardia, rhodococcus.

Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology # Volume III:

Section 18: Anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria.

(I) Purple bacteria

Family I: Chromatiaceae e.g., chromatium .

Family II: Ectothiorhodospiraceae, Ectothiorhodospira.

(II) Purple Non sulphur bacteria Rhodospirillum, Rodobacter.

(III) Green Bacteria:

Green sulphur bacteria e.g., chlorobium, chloroberpeptone.

(IV) Multicellular, Filamentous, green bacteria e.g., Chloroflexus, heliothrix.

(V) Genera Incertae sedis Heliobacterium, Erytherobacter.

Section 19: Oxygenic photosynthetic bacteria Cyanobacteria.

Family I: Chrococcaceae.

Family II: Pleurocapraceae.

Family III: Oscillatoriaceae e.g., spirulina, oscillatoria

Family IV : Nostocaceae e.g., Anabena, Nostoc.

Family V: Stigonemataceae e.g., Chlorogloeopsis.

B: Prochloraceae e.g., Prochloron.

Section 20: Aerobic Chemolitholrophic bacteria and associated organisms.

A. Nitriflying bacteria.

Family: Nitrobaacteriaceae e.g., Nitrobacter, Nitrococcus, Nitrosomonas.

B. Colourless Sulphur bacteria, e.g., Thiobacterium, Macromonas, Thiospira.

C. Obligately chemolithtrophic, Hydrogen bacteria e.g., Hydrogenobacter.

D. Iron and manganese oxidizing and/or depositing bacteria e.g.,

Family: Siderocapsaceae e.g., Siderocapsa.

E. Magnotactic bacteria, e.g., Aquaspirillum, Maganotacticum.

Section 21: Budding and/or Appendaged bacteria

1. Prosthecate Bacteria.

A. Budding Bacteria, Genus, Hyphomonas, Prosthecomicrobium.

B. Non budding bacteria, Caulobacter, Prosthecobacter.

2. Nonprosthecate bacteria.

A. Budding bacteria lack peptidoglycan, planctomyces, contain peptidoglycan e.g., Blastobacter.

B. Non-budding bacteria e.g., Galionella, Nevskia.

Section 22: Sheathed Bacteria, e.g., Sphaerotilus, Leptothrix, clonothrix.

Section 23: Nnphotsynthetic, non-fruiting Gliding bacteiua.

Family I: Cytophagaceae, e.g., cytophaga.

Family II: Lysobacteriaceae e.g., Lysobacter.

Family III: Beggiatoaceae e.g., Beggiatoa, Thiothrix, Thioploca.

Other families:

Family: Simonriellaceae e.g., Simonsiella.

Family: Pelonemataceae, e.g., pelonema.

Section 24: Fruiting Gliding bacteria (Myxobacteria).

Family I: Myxococcaceae e.g., Myxococcus.

Family II: Archangiaceae e.g., Archangium.

Family III: Cystobacteriaceae e.g., Cystobacter.

Family IV : Polyangiaceae e.g., Polyangium.

Section 25 : Archaebacteria.

Group I : Methanogenic archae bacteria.

Family I: Methanobacteraceae e.g., Methanobacterium.

Family II: Methanothermaceae e.g., Methanthermus.

Family III: Methanomicrobiaceae e.g., Methanomicrobium.

Family IV : Methanosarcinaceae e.g., Methanosarcina.

Family V : Methanplanaceae e.g., methanoplanus.

Group II : sulphate reducer Archace bacteria.

Family : Archaeoglobaceae e.g., Archaeoglobus.

Group III: Extrenely halophilic Archaebacteria.

Family : Halobacteriaceae e.g., Halobacterium.

Group IV : Cell wall less archaebacteria.

Family: Thermoplasmaceae.

Group V: Extremely thermophilic sulphate metabolizers. Family: Thermococcaceae e.g.,Thermocccus.

Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology # Volume IV:

Section 26: Nocardioform actinomeycetes e.g., Nocardia, Rhodococcus.

Section 27: Actinomycetes with multi-locualar sporangia e.g.,. Frankia, Dermatophilus.

Section 28: Actinoplanetes e.g., Actonoplanes, Micromonospora.

Section 29: Streptomycetes and related genera a e.g., streptomyces, Kineosporia.

Section 30: Maduromycetes, e.g., actinomadura, Streptosporangium.

Section 31: Thermomonospora and related genera e.g., Nocardiopsis.

Section 32: Thermactinomycetes e.g., Thermoactimoneyces.

Section 33: Other genera e.g., Glycmyces, Pasteuria, Saccharothrin.

Related Articles:

How does one go about identifying an isolate when there are well over 400 known bacterial genera and more than 35,000 identified species? Fortunately, the American Society for Microbiology (originally the Society of American Bacteriologists) has for decades published a compilation of known bacteria, first as Bergey's Manual of Determinative Bacteriology and more recently as Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology.

Multiple editions of Bergey's Manual of Determinative Bacteriology, published between 1923 and 1994, organized bacteria in groups by phenotypic characteristics, with no attempt to sort out higher phylogenetic relationships. They were very useful for identifying unknown bacterial cultures, however. In lab, you will use the most recent edition of Bergey's Manual of Determinative Bacteriology, published in 1994 and reprinted in 2000, to help you identify your isolates.

The first edition of Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, which came out in four volumes from 1984 through 1989, attempted to organize bacterial species according to known phylogenetic relationships, an approach that continued with a second edition, published in five volumes from 2001 through 2012. The organization of Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology makes it impractical for helping place unknown bacteria into major taxa, but it contains far more detail on the families, genera, and species and is far more up to date than the Determinative manual. You will need to consult this information in order to double check and finalize your identifications.

Using the Determinative manual

We have enough copies of the physical manual to issue one copy per team of three or four students. We will require a $40 refundable deposit to cover loss of the volume if it is not returned. Please read the rest of this page after your team has obtained its copy.

Read over Chapters I and II, which describe how to approach identification of a bacterial isolate. Chapter V of the Manual provides descriptions of all of the major Groups of bacteria, organized by phenotype. The following observations, listed in order of importance, will help you identify the Group to which your isolate most likely belongs. Remember, you must have a pure culture before conducting these observations.

Observations to be conducted on all isolates

Gram positive or Gram negative. The Gram stain result (positive or negative) is the single most important step in differentiating major taxa. You must be certain of this result or your identification effort may be doomed from the start. See the document on preparing and interpreting Gram stains (Gram_stain.asp) for more details

Relationship to oxygen. It is critical that you correctly identify your isolate as either an obligate aerobe (requires oxygen), a facultative anaerobe (can grow w/o oxygen), or a microaerophil. Microaerophils, which grow only in the presence of low partial pressures of oxygen, are uncommon but will grow in our laboratory. We will not find obligate anaerobes, which cannot grow in the presence of oxygen.

Bergey's Manual Chart

Cell morphology. Cocci are spherical or nearly sperical bacterial cells that might also be described as coccoid. A bacterial rod has definite long and short axes, resembling a cylinder, often with rounded ends. We also have curved bacteria, and less commonly spiral or helical bacteria (having at least one full turn), branching cells, budding cells, club shaped cells, and cells with stalks.

Bergey's Manual Identification Chart

Cell aggregations. Cells might appear singly, in pairs, in tetrads, in clusters, in long or short chains, etc.

Cell dimensions. With the exception of true cocci, individual cells of a pure culture typically vary widely in length, though not usually in diameter. At 1000x we can estimate a dimension to the nearest 1/2, maybe 1/3 of a micrometer.

Motility. Does a wet mount of living bacteria reveal active movement? Use motility as a criterion for choosing a group, but not for ruling out a group. Some motile species are notorious for not revealing motillity under the microscope. You are strongly advised to record your observations as 'motile' or 'motility not observed,' never simply as 'nonmotile.'

Oxidase test. The oxidase test checks for the presence of cytochrome oxidase, used in oxidative metabolism. It is particularly useful for distinguishing groups of Gram negative organisms. We run the test on all of our isolates because it is very quick and inexpensive, although it may not be a useful differential characteristic for all of your isolates.

Catalase test. This one tests for the presence of an enzyme, catalase, that destroys oxygen radicals, toxic byproducts of an oxidative metabolism. Like the oxidase test, this one will be helpful in identifying some of your isolates, but probably not all. It is, however, very cheap, fast, and easy to do.

Colony characteristics. Characteristics such as color, texture, margin, etc. are useful for confirming that you are in the correct taxonomic group. See the document on describing colony morphology (describing_colonies.asp) for details.

Narrowing down the possible taxa

Your initial phenotypic observations should enable you to place each of your isolates into one or perhaps two Groups of bacteria. From there, you should be able to conduct additional assays and observations that lead you to a specific genus and (hopefully) species. The introduction to each Group chapter refers to a table of differential characteristics, which will be your starting point. Use the table to narrow your choices to a few or even just one taxon, then continue logically from there. As you proceed:

- Ensure that you start with a pure culture

- Start with the broadest categories and work down to smaller more specific categories of bacteria

- Use common sense as you proceed

- Use the minimum number of tests needed to make an identification

- Be aware of possible complications associated with each test

- If available, compare the isolate to the appropriate type strain in the laboratory

The results of some assays will vary with size of inoculum, temperature, time of incubation, type of medium, gas content of the medium, etc. Some subjectivity may be involved, for example, positive and negative tests may be difficult to distinguish at times. Furthermore, different strains of some species may give different results. Frequently it is more important to recognize the pattern of results than to rely heavily on results of one or two tests.

In the tables, the most discriminatory tests are listed first, so it is advisable to work from the top down once a category is established. Below is a key to the symbols used in the tables.

90% or more of strains are positive | |

- | 90% or more of strains are negative |

| 11-89% of strains are positive | |

v | strain instability (not the same as 'd') |

| different reactions in different taxa |

Using the Systematic manual (on line)

The primary purpose of this five volume set to provide detailed information on bacterial classification and detailed characteristics of taxa and species. The volumes are organized according to molecular classification systems including 16s RNA sequences rather than by phenotypic characteristics, making them of little use in systematically identifying isolates. The manual will, however, be very valuable for obtaining detailed information once you have narrowed your search.

Bergey's Manual Flow Chart

- Considering our sources of bacteria you are unikely to need Volume 1.

- Volume 2 of the Manual covers the Proteobacteria (most gram negative bacteria) in three parts. The majority of gram negatives will be found in part B. Look in part C if a description of your species is not in volume 2B.

- Volume 3 covers the Firmicutes (most of the gram positive bacteria).

- Volume 4 covers a variety of other bacteria including the spirochaetes, a species of which we found in pond water some years ago.

- Volume 5 includes the Actinobacteria (gram positive bacteria with high G+C content); if you cannot find your Gram + species in the index to Vol. 3 then you might try here.

Volumes 2-5 are availalbe on line to any Rice student by logging in to the Fondren Library web page using your netID and password. To access the online Manual start with the Fondren Library home page (http://library.rice.edu/).

Bergey's Manual Chart

- In the drop-down menu under Catalog, select OneSearch

- Type 'bergey's ' in the field at the very top and hit return or enter or click on Search

- Scroll down to the Bergey's volume that you want and click on the 'online access' link (not on the volume title)

- Click on the Read Online button

Bergey's Manual Chart Gram Positive Rod

When you think you have identified the species look it up in the index and review the descriptions of both the genus and the species itself. You are strongly advised to use the Index to search directly for your species rather than to try to browse the volume. To the left are the book's contents. Scroll all the way down to quickly get to the index of scientific names. Note that a page number in boldface type denotes a page on which descriptive information is found. Page numbers not in boldface refer to mere mention of the taxon (often as part of a citation) and are not likely to include useful information for you.

If you have trouble finding your species

If your genus/species is listed in the index but there are no page numbers in boldface type, then you are definitely in the wrong volume. A Google search of the genus or species usually turns up a page that gives taxonomic information. Wikipedia listings, for example, may have a column titled 'Scientific classification' that lists kingdom, phylum, class, order, family, and genus. Phylum and class will direct you to the correct Bergey's volume.

If your genus/species is not listed in the index at all, then either you are in the wrong volume, your species has been reassigned to a new genus, or both. Based upon what we have learned about phylogenetic relationships since the 1994 publication of the last Determinative volume, many species have been reassigned to different genera and whole new genera created. If there has been a name change then a Google search should turn up the information you need in order to find the Bergey's volume and listing. For example, in the Determinative manual, under Group 17 Gram-Positive Cocci, you will find the genus Micrococcus. Some species under Micrococcus have been reassigned to Kocuria.